Pituitary Tumour

The pituitary tumour produces a variety of mass effects, depending on their size and location, but also present as incidental findings on CT or MRI, or with hypopituitarism.

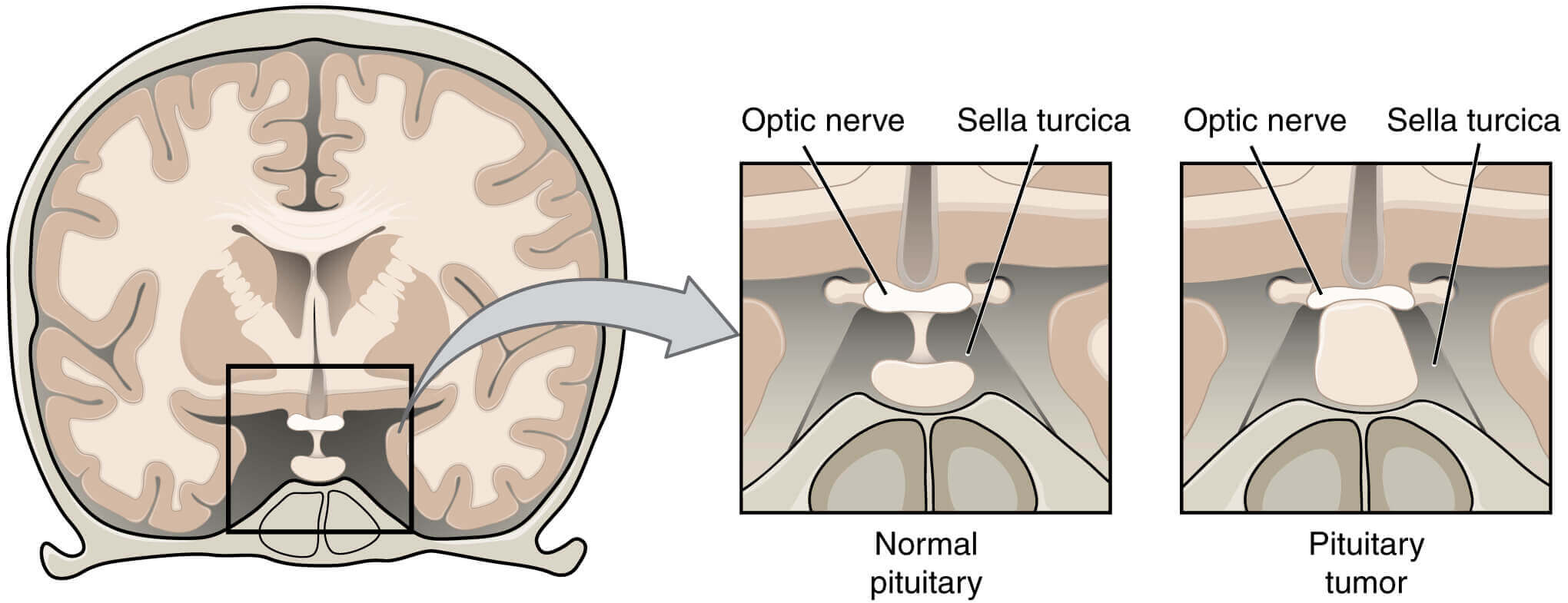

A wide variety of disorders can present as mass lesions in or around the pituitary gland. Most intrasellar tumours are pituitary macroadenomas (most commonly non-functioning adenomas; whereas suprasellar masses may be craniopharyngiomas.

The most common cause of a para sellar mass is a meningioma.

Clinical assessment

Clinical features are shown in Figure 18.28. A common but non-specific presentation is with headache, which may be the consequence of stretching of the diaphragm sellae.

Although the classical abnormalities associated with compression of the optic chiasm are bitemporal hemianopia. or upper quadrantanopia, any type of visual field defect can result from suprasellar extension of a tumour because

it may compress the optic nerve (unilateral loss of acuity or scotoma) or the optic tract (homonymous hemianopia). Optic atrophy may be apparent on ophthalmoscopy.

The lateral extension of a sellar mass into the cavernous sinus with subsequent compression of the 3rd, 4th or 6th cranial nerve may cause diplopia and strabismus, but in anterior pituitary tumours, this is an unusual presentation.

Occasionally, pituitary tumours infarct or there is bleeding into cystic lesions. This is termed ‘pituitary apoplexy’ and may result in sudden expansion with local compression symptoms and acute-onset hypopituitarism.

Non-haemorrhagic infarction can also occur in a normal pituitary gland; predisposing factors include catastrophic obstetric haemorrhage (Sheehan’s syndrome), diabetes mellitus and raised intracranial pressure.

Investigations

Patients suspected of having a pituitary tumour should undergo MRI or CT. While some lesions have distinctive neuro-radiological features, the definitive diagnosis is made on histology after Surgery. All patients with (para)sellar space-occupying lesions should have pituitary function assessed.

Management of Pituitary tumour

Modalities of treatment of common pituitary and hypothalamic tumours. Associated hypopituitarism should be treated as described above.

Clamorous treatment is required if there is evidence of pressure on visual pathways.

The chances of recovery of a visual field defect are proportional to the duration of symptoms, with full recovery unlikely if the defect has been present for longer than 4 months. In the presence of a sellar mass lesion, it is crucial that serum prolactin is measured before emergency surgery is performed.

The prolactin is over 5000mlU/L (236 ng/mL), then the lesion is likely to be a macroprolactinoma and should respond to a dopamine agonist with shrinkage of the lesion, making surgery unnecessary.

Most operations on the pituitary are performed using the trans-sphenoidal approach via the nostrils, while transfrontal surgery via a craniotomy is reserved for suprasellar tumours and is much less frequently needed.

It is uncommon to be able to resect lateral extensions into the cavernous sinuses, although with modern endoscopic techniques this is more feasible. All operations on the pituitary carry a risk of damaging normal endocrine function; this risk increases with the size of the primary lesion.

Pituitary responsibility should be retested 4-6 weeks following surgery, primarily to detect the development of any new hormone deficits. Rarely, the surgical treatment of a sellar lesion can result in the recovery of hormone secretion that was deficient pre-operatively after a while surgery, usually, after 3-6 months, imaging should be repeated.

If there is a significant residual mass and the histology confirms an anterior pituitary tumour, external radiotherapy may be given to reduce the risk of recurrence but the risk: benefit ratio needs careful individualised discussion.

Radiotherapy is not useful in patients requiring urgent therapy because it takes many months or years to be effective and there is a risk of acute swelling of the mass. a life-long risk of hypopituitarism (50-70% in the first 10 years) and annual pituitary function tests are obligatory.

There is also concern that radiotherapy might impair cognitive function, cause Fractionated radiotherapy carries vascular changes and even induce primary brain tumours. but these side-effects have not been quantified reliable and are likely to be rare. Stereotactic radiosurgery allows specific targeting of residual disease in a more focused fashion.

Non-functioning tumours should be followed up by repeated imaging at intervals that depend on the size of the lesion and on whether or not radiotherapy has been administered.

For smaller lesions that are not causing mass effects, therapeutic surgery may not be indicated and the lesion may simply be monitored by serial neuroimaging without a clear-cut diagnosis having been established.