Abdominal Compartment Syndrome

What is abdominal compartment syndrome?

Abdominal compartment syndrome (ACS; Richards and Krons, 1984) is organ dysfunction caused by increased intra-abdominal pressure of more than 12 mmHg (intra-abdominal hypertension/IAH); organ dysfunction is usually respiratory, cardiovascular, and renal but can be any organ; normal intra-abdominal pressure is being considered as 2-7 mmHg.

Abdominal perfusion pressure (APP) is the pressure that maintains adequate abdominal blood flow. It is measured by subtracting the intra-abdominal pressure (IAP) from mean arterial pressure (MAP). APP in ACS is usually less than 60 mmHg but should be maintained as more than 60 mmHg.

Effects of ACS

The effects of abdominal compartment syndrome are:

- Cardiovascular system: It is often sudden, and rapidly progressive, decreasing the venous return (due to IVC compression) to the heart and increased peripheral resistance, with decreased right atrial pressure and decreased cardiac output.

- Respiratory system: Intrapleural pressure is increased proportionately to the abdominal pressure. Upward displacement of the diaphragm, increased peak inspiratory pressure, hypoxia, hypercapnia, acidosis, respiratory failure, ARDS are other problems. It also causes restrictive lung disease.

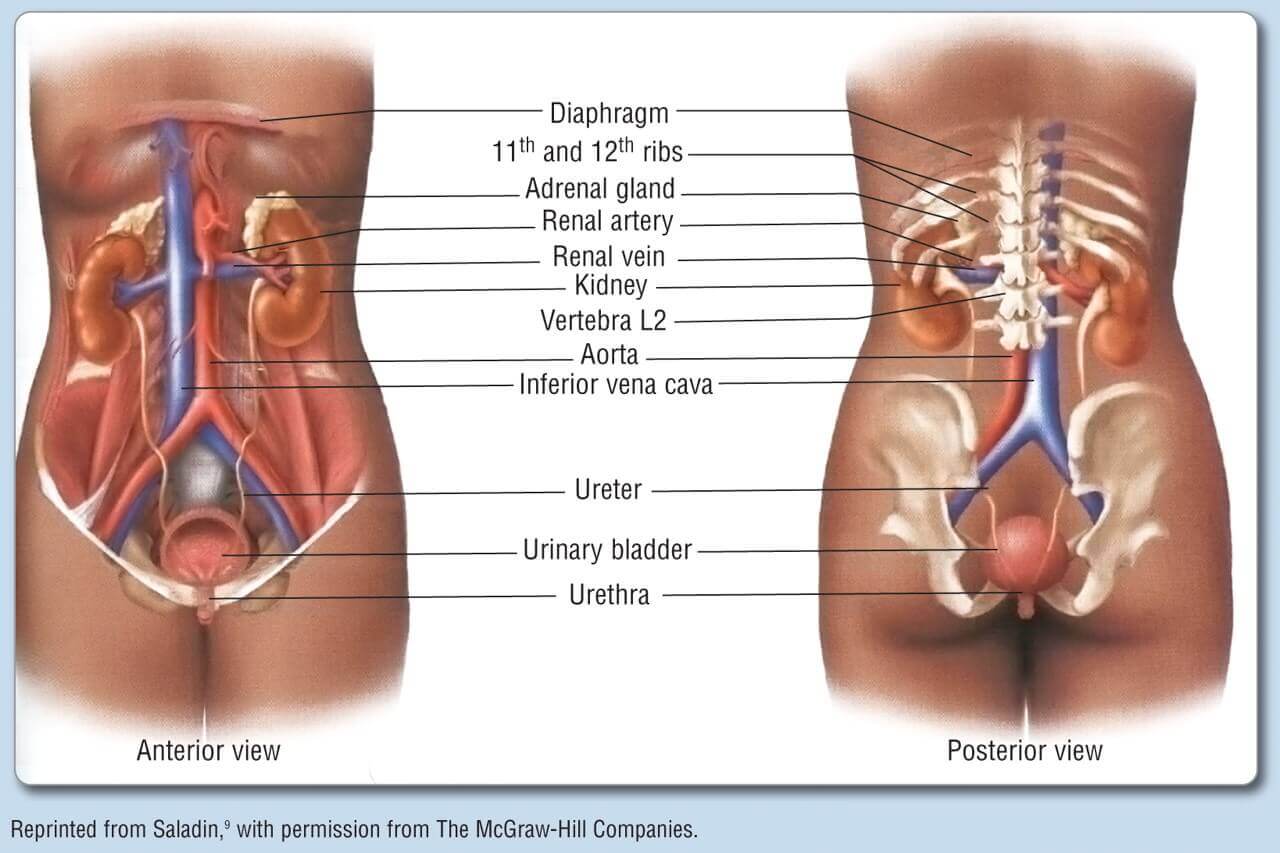

- Renal system: Decreased renal blood flow and glomerular filtration cause oliguria, renal failure.

- Gastrointestinal system: Mesenteric venous hypertension; bowel wall oedema and ischaemia. Central nervous system: Cerebral oedema and hypoxia, unconsciousness.

Causes of Abdominal Compartment Syndrome

The causes of abdominal compartment syndrome are:

- Major abdominal trauma, postoperative abdominal hemorrhages, after damage control surgery with abdominal packings, are the common causes; of ruptured aortic aneurysm.

- Closure of the abdomen under tension; forcible reduction of the massive hernia.

- Bowel wall edema, mesenteric congestion, acute ascites; profound hypothermia and coagulopathy.

- Acute gastric dilatation, paralytic ileus, gastroparesis, colonic pseudo-obstruction.

- Retroperitoneal hemorrhages, pancreatitis.

- Laparoscopic procedures.

- Morbid obesity, pregnancy, major burns, and continuous ambulatory peritoneal dialysis are precipitating causes.

Epidemiology

Abdominal compartment syndrome (ACS) can develop in all intensive care unit patients. In an identified series of mixed ICU populations, 35% of ventilated patients were found to have intraabdominal hypertension (IAH) or ACS.

For patients with visceral injuries, ACS prevalence ranged from 1.0% to 20.0%; one study in the second period reported 11.1%.

The prevalence among severely injured patients who underwent trauma laparotomy ranged from 0.9% to 36.4% in the first period.

Features and Diagnosis of Abdominal Compartment Syndrome

- Tensely distended abdomen, progressive oliguria, airway obstruction, occult blood loss.

- Measurement of urinary bladder pressure: Transducer and manometer methods are available. The bladder acts as a passive reservoir at volume less than 100 ml (now 25 ml saline is used to measure) and it can transmit IAP without imparting any additional pressure from its bladder musculature.

Measurement of bladder pressure reflects the IAP pressure. IAP is measured using a urinary catheter in the urinary bladder. The pressure is graded (Burch) as I—10-15 cm of H2O (will not require decompression); II— 16-25 cm of H2O (needs close monitoring); III—26-35 cm H2O (most need decompression); IV—more than 36 cm H2O (all need decompression otherwise will die of cardiac arrest in few hours). Beyond grade, Ill immediate decompression is needed. Initial volume preload is essential otherwise sudden decompression may cause cardiac arrest in asystole due to reduced preload, the sudden influx of high potassium, acid and other metabolic by-products into the heart. Grade III and IV become a surgical emergency. - Chest X-ray, ECG monitoring, ICU care, electrolytes, hematocrit and serum creatinine estimation, USG abdomen should be done.

- Mortality for ACS is 40%.

Intraabdominal pressure

| Intra-abdominal pressure grading | Burch grading in cm of water | World Society Of the ACS in mm of Hg (Muckart et al., and Malbrain et al.) |

| I | 10-15 cm of H2O | 12-15 mmHg |

| II | 15-25 cm of H2O | 16-20 |

| III | 25-35 cm of H2O | 21-25 |

| IV | >35 | ≥25 |

| Abdominal Compartment Syndrome (ACS) |

| Causes Multiple trauma and ICU patients Postoperative ileus Acute abdomen Acute gastric dilatation Laparoscopic procedures Intestinal obstruction Major burns | Features Hypoxia Hypercarbia Decreased urine output anuric renal failure in severe cases Tense abdomen – distended Decreased venous return Refractory hypoxeamia in severe cases Bowel ischemia Cardiac arrest | Management Bladder pressure assessment Ryle’s tube aspiration Resuscitation ICU care Surgical decompression |

Differential diagnosis

The DD of abdominal compartment syndrome are:

- Mesenteric ischaemia

- Ruptured abdominal aortic aneurysm

- Toxic megacolon

- Acute appendicitis

- Acute diverticulitis

- Acute pancreatitis

Treatment

- Abdominal decompression is the only ideal treatment for ACS; technique and timings are decided based on the clinical situation.

- Temperature and coagulation profile should be made as possible as normal prior to decompression.

- Silastic sheet created chimneys sutured to fascia around is often used. Pressure-free abdominal closure should be the target. Bogota bag, first described by Londoni, chief resident in Bogota, Columbia is cost-effective; here irrigation bags are sutured to each other as necessary to get a proper size and is sutured to fascia around using 1 zero nylon suture. Several litres of serosanguineous or ascitic fluid is let out through a plastic stoma bag attached to a closed drainage system. Once a patient is haemodynamically stable, definitive closure is performed after 48 hours. Abdominal fascia is closed using nonabsorbable sutures; subcutaneous tissue and skin are closed at a later period. Fluid and electrolyte management, antibiotics, adequate blood or blood product transfusions should be used as needed.

- Other methods of closure: Towel clips, temporary mesh placement; PTFE mesh repair; vacuum-assisted closure are all temporary closure methods. Definitive closure methods

Primary closure of fascia; closure using synthetic mesh if no sepsis in the wound; biological mesh closure; component separation technique; closure using skin graft or flaps.

Complications of abdominal compartment syndrome

- Renal failure

- Bowel ischemia

- Respiratory distress

- Increases cranial pressure

- Low cardiac output and shock

Summary

Abdominal compartment syndrome occurs when the abdomen becomes subject to increase the pressure. The mortality rate blend with abdominal compartment syndrome is significant, ranging between 60% and 70%.

The poor outcome relates not only to abdominal compartment syndrome itself but also to concordant injury and hemorrhagic shock.

Frequently Asked Questions

What causes increased intraabdominal pressure?

High intraabdominal pressure (IAP) frequently occurs in patients with acute abdominal syndromes such as ileus, intestinal perforation, peritonitis, acute pancreatitis, or trauma. An elevated IAP may lead to intraabdominal hypertension (IAH) and abdominal compartment syndrome (ACS)

How do you relieve Intraabdominal pressure?

Lift properly with inward contraction of abdominals and outward breath on effort. Avoid bulging the abdominals outward and bearing down. Exercise correctly using an inward abdominal contraction. Avoid taking down and pouching the abdominal muscles outward.

Why is inter abdominal pressure necessary

The lower, the IAP, the lower the risk of abdominal compartment syndrome. The higher the IAP, the higher the risk of abdominal syndrome. It is important to note that the signs and symptoms of abdominal compartment syndrome worsen with increasing intra-abdominal pressure.

What is intravesical pressure?

Intravesical pressure: the pressure recording from a urodynamic catheter placed inside the bladder. Physiological filling rate (during cystometry) that is less than the predicted maximum.