Ways to prevent life-threatening Fever of Unknown Origin

How to deal with Fever of Unknown origin?

The title fever of unknown origin is foremost aloof for children with a fever documented by a healthcare provider. For which the cause could not be identified after 3 weeks of estimation as an outpatient or after 1 week of evaluation in the hospital. Fever of unknown origin (FUO) is also known as pyrexia of unknown origin (PUO).

Patients with pyrexia not meeting these criteria and specifically those admitted to hospital with neither an apparent site of infection nor a noninfectious diagnosis may be considered to have a fever without localizing signs.

Causes of fever of unknown origin:

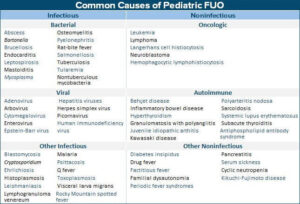

- Infections: Enteric fever, malaria, UTI, tuberculosis, chronic hepatitis, HIV infection, hidden abscesses (liver, pelvic), mastoiditis, sinusitis, osteomyelitis, meningitis, infectious mononucleosis, infective endocarditis, brucellosis, cytomegalovirus, toxoplasmosis, kala-azar.

- Autoimmune: Systemic onset juvenile rheumatoid arthritis, SLE, polyarteritis nodosa, Kawasaki disease, inflammatory bowel disease.

- Malignancies: Leukemia, lymphoma, Langerhan cell histiocytosis.

Most fevers of unknown origin or masquerading origin or pyrexia of unknown origin (PUO) result from atypical presentations of common diseases.

In some cases, the presentation as an FUO is characteristic of the disease, such as juvenile rheumatoid arthritis (JRA), but the definitive diagnosis can be established only after prolonged observation because initially there is no associated or specific finding on physical examination and all laboratory results are negative or normal.

Drugs fever is not unusual in children. Infections account for most of the cases of FUO in children (60-70%). Even with extensive investigations, the cause of FUO remains undiagnosed in 10-20% of the cases.

Diagnostic Approach to FUO

The first step is to identify sick patients who need stabilization and urgent referral to a tertiary care centre. Subsequently, all attempts should be made to reach an etiologic diagnosis. A detailed history is of paramount importance. History should include the following:

- Where and how fever was documented.

- Duration and pattern of fever (distinguish from recurrent fever).

- Symptoms are referable to all organ systems, weight loss.

- History of recurrent infections, oral thrush (HIV infection).

- History of joint pains, rash, photosensitivity (an autoimmune disease).

- History of contact with tuberculosis and animals (brucellosis).

- Travel to endemic zones (kala-azar).

- Drug history particularly anticholinergics (drug fever).

- History of pica, ingestion of dirt could be an important clue towards the diagnosis of Toxocara or Toxoplasma gondii

Physical Examination for PUO

Careful and meticulous physical examination is mandatory in all children who have an undiagnosed fever. Repetitive examination, preferably daily, is also important to pick up subtle or new signs, which may appear during the illness.

- Sweating: The continuing absence of sweat in the presence of an elevated or changing body temperature suggests dehydration due to vomiting, diarrhoea, or central nephrogenic diabetes insipidus.

- A careful ophthalmic examination:

- Red, weeping eyes-connective tissue disease, particularly polyarteritis nodosa.

- Palpebral conjunctivitis-measles, coxsackievirus infection, tuberculosis, infectious mononucleosis, lymphogranuloma venereum, and cat-scratch disease.

- Bulbar conjunctivitis-Kawasaki disease or leptospirosis.

- Petechial conjunctival hemorrhages-infective endocarditis.

- Uveitis-sarcoidosis, JRA, systemic lupus erythematosus, Kawasaki disease, Behçet disease, and vasculitis.

- Chorioretinitis CMV, toxoplasmosis, and syphilis.

- Proptosis orbital tumour, thyrotoxicosis, metastasis (neuroblastoma), orbital infection, Wegener granulomatosis, or pseudotumor.

- Tenderness to tapping over the sinuses or the upper teeth suggests sinusitis.

- Recurrent oral candidiasis may be a clue to various disorders of the immune system.

- Fever blisters-common findings in patients with pneumococcal, streptococcal, malarial, and rickettsial infection meningococcal meningitis (which usually does not present as FUO), rarely are seen in children with meningococcemia, Salmonella or staphylococcal infections.

- Hyperemia of the pharynx, with or without exudate infectious mononucleosis, CMV infection, toxoplasmosis, salmonellosis, tularemia, Kawasaki disease, or leptospirosis.

- Point tenderness over a bone-occult osteomyelitis bone marrow invasion from the neoplastic disease.

- Tenderness over the trapezius muscle-may be a clue subdiaphragmatic abscess.

- Generalized muscle tenderness-dermatomyositis, polyarteritis, Kawasaki disease, or mycoplasmal or arboviral infection.

- Rectal examination-perirectal lymphadenopathy or tenderness, which suggests a deep pelvic abscess, iliac adenitis or pelvic osteomyelitis.

- Occult blood loss may suggest granulomatous colitis or ulcerative colitis as the cause of FUO.

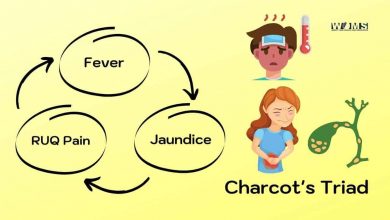

- Repetitive chills and temperature spikes-septicemia (regardless of cause), particularly when associated with renal disease, liver or biliary disease, infective endocarditis, malaria, brucellosis, drug fever, rat-bite fever, or a loculated collection of pus.

- The general activity of the patient and the presence or absence of rashes should be noted.

- Hyperactive deep tendon reflexes may suggest thyrotoxicosis as the cause of FUO.

- Careful palpation for all groups of lymph nodes and detection of hepatic and splenic enlargement may be vital to follow the appropriate line of investigation.

However, a physical examination is not always conclusive in defining the cause of a prolonged fever so that investigations are always necessary to determine the diagnosis and to confirm the aetiology.

Investigations of fever of unknown origin

- CBC, ESR, PBF, MP, MT, gastric washings for AFB; serology: Widal, aldehyde triple antigen), RA, ANA.

- Tests for brucella, salmonella, rickettsiae (test for a febrile triple antigen), RA, ANA.

- Chest X-ray, urine analysis, blood and urine cultures, stool examination, LFT, and CSF analysis.

- Liver biopsy

- Ultrasound examination, IVU, bone marrow aspiration, and biopsy; FNAC/biopsy of the lymph node.

Treatment for pyrexia of unknown origin

- As far as possible, any sort of treatment for FUO should be started only when sufficient grounds for the diagnosis are not available; mild antipyretics (paracetamol + tepid sponging) may be given. Hydration should be maintained. Empirical trials with antibiotics may mask the diagnosis of subacute bacterial endocarditis, meningitis, or osteomyelitis, In general, observation of the temperature pattern repeated clinical examination, and careful laboratory evaluation and interpretation of the results might throw light on the diagnosis.

- Specific treatment depends on the diagnosis.

- Empirical treatment is generally avoided, except in critically ill patients where anti-TB treatment can be given in suspicion of disseminated TB.